Georgia – The Secret Birthplace of Wine

Georgians are rightly proud of their rich and historic winemaking culture, and as traditional methods enjoy a renaissance, the Qvevri – an earthenware vessel used to store and age wine for thousands of years – is becoming the unofficial symbol of the country. Though only around three per cent of Georgia’s wines are made in these Qvevri, they remain a romantic ideal that celebrates the country’s history.

Georgia is generally considered the ‘cradle of wine’, as archaeologists have traced the world’s first known wine creation back to the people of the South Caucasus in 6,000BC. These early Georgians discovered grape juice could be turned into wine by burying it underground for the winter. Some of the Qvevris they were buried in could remain underground for up to 50 years.

Wine continued to be important to the Georgians, who incorporated it into art and sculpture, with grape designs and evidence of wine-drinking paraphernalia found at ruins and burial sites.

One look at the countryside and you will understand why wine is revered in this place. With fertile lands, a healthy climate, and good irrigation systems, Georgia is a winemaker’s playground. Their lands happen to be home to the most varietals in the world, amounting to around 400 grape varieties.

The tumultuous years around the Soviet period were initially good for Georgian wine production. The wines were significantly better than others available to the Russians and the number of acres used for vine-growing increased massively. But in the 1980s, former Russian President Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign cut off some of the older wineries. Since then, Russian embargoes on wine have harmed production and it has taken decades for the industry to rebuild after independence.

Today, Georgia remains a relatively small producer, but that may be about to change in the decades to come

Natural Wine in Modern Georgia

Georgia is now making a name for itself in the natural wine market. Even though it’s a small amount of its total production, the rise in interest for traditional methods and using clay for storage and fermentation has put the country back at the forefront of wine production.

The Georgians pride themselves in preserving the practice of ageing wines in jars called Qvevri. A Qvevri is a large, egg-shaped clay vessel with a narrow bottom and wide mouth at the top. Though researchers believe the earliest Qvevri were stored above ground, Georgian winemakers for millennia have buried their Qvevri, with only the vessel’s rim visible above the ground. Scholars say the word Qvevri comes from Kveuri, which means “that which is buried” or “something dug deep in the ground.”

Qvevris are uniquely Georgian, different in shape and function from the clay amphorae used elsewhere. Used for wine fermentation, maturation, and storage, Qvevri are among the world’s earliest examples of winemaking technology. Archaeologists date the oldest known winemaking Qvevri—discovered in a Neolithic settlement in eastern Georgia in 2015—to 6000 BC. These vessels are not only important historical artefacts but also signify the early evidence of an enduring cultural tradition.

Modern Qvevri typically ranges in size from 100 litres to 3,500 litres. The largest Qvevri are big enough for a person to climb into—which is what the winemaker does when it’s time to clean a vessel. The tradition of making wine in Qvevri is so embedded in Georgian culture that in 2013 UNESCO added it to its catalogue of humanity’s intangible cultural heritage. This marked the Qvevri a symbol of the deep cultural roots of Georgian wine and the authenticity of Georgian winemaking.

A Peek into Qvevri Winemaking

Winemakers using the traditional Qvevri method follow the same basic process and principles Georgians developed 8,000 years ago—skins and stems in the vat, natural yeasts, natural tannins. These are the main steps:

1. Cleaning. The process starts with a clean, well-rinsed Qvevri. Traditionally, a worker scoops out the solids at the bottom of an emptied vessel, then climbs inside to scrub the walls. Then the Qvevri is washed out with an alkaline solution and rinsed several times until the water runs clear.

2. Crushing. After sorting the grapes, the winemaker crushes the bunches in a traditional stone or wooden wine press, called a Satsnakheli. The grape must is then loaded into the Qvevri, typically with all or part of the marc and stalks, to three-quarters of the vessel’s capacity. The grapes can be either red or white, but the best-known traditional Georgian wines are the amber wines produced in Qvevri from white grapes. (Red grapes are typically destemmed at this stage.)

3. Fermentation. Fermentation takes place without intervention, using naturally occurring yeasts and natural (underground) temperature control. Producers typically punch down the cap and stir the vat during fermentation.

4. Sealing the Qvevri. When the cap starts to sink and producers determine fermentation is complete, they seal the Qvevri with a lid (stone, glass, or metal) and a clay or silicone sealer.

5. Maturation. Producers leave the solids to macerate in the Qvevri for the first three to six months of the wine’s ageing before removing them. (This period is shorter with red wines and some white wines.) Producers who want malolactic conversion to take place during fermentation (especially with red wines) sometimes warm the Qvevri with a heating element before racking the wine off the lees. The Qvevri’s sloped walls allow the yeast and sediment to settle at the bottom while the wine circulates above.

6. Storage. In the spring, when the wine is ready, the winemaker either bottles it or transfers it to another Qvevri for short-term storage—since Georgian wine is often consumed before the next harvest—or an extra year of ageing.

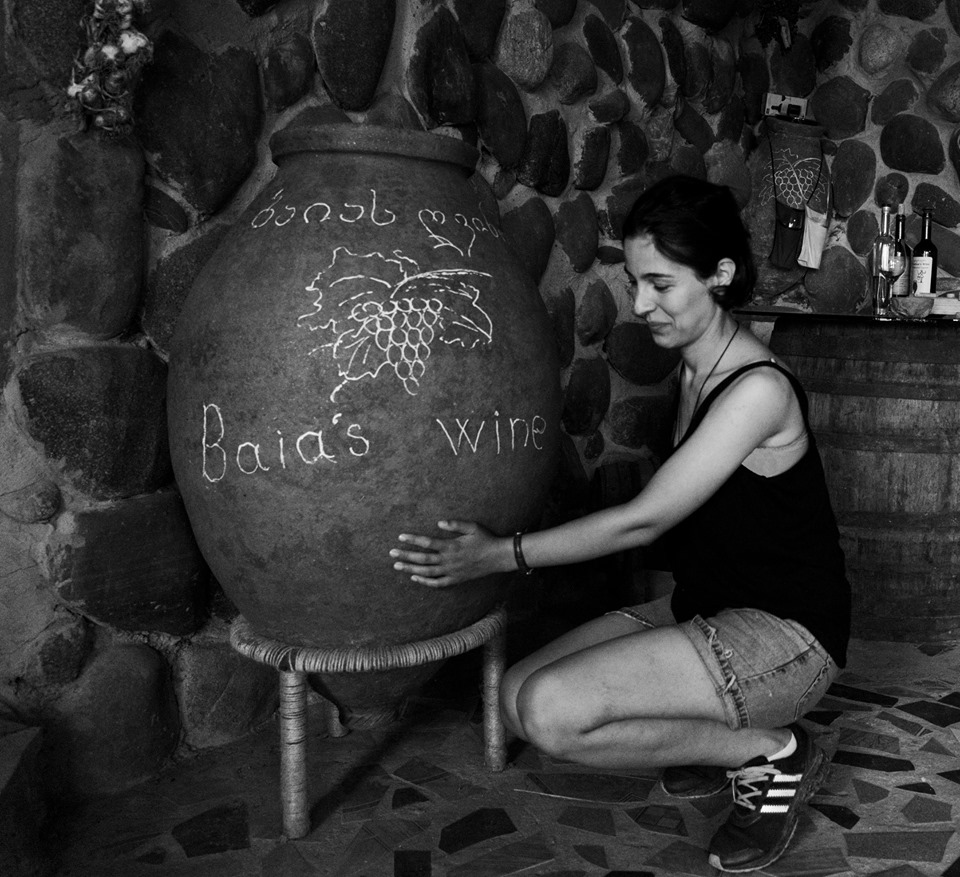

Introducing Baia’s Vineyard

Georgia, Imereti, Obcha Village

Baia’s Wine is a small, tight-knitted winery created out of a passion for their land while bringing new life and energy to a region with plenty of history. Because of the new life and energy they brought to the winemaking scene, owners and young sisters Baia (left) and Gvantsa Abuladze (right) quickly became well-known names not just in Georgia, but also outside of their homeland.

In 2015 and in their early 20’s, the sisters decided to continue their family traditions of winemaking in the beautiful village of Obcha, Imereti of Western Georgia. The sisters of Baia followed in their parent’s and grandparent’s footsteps, making exquisite wines with the Georgian traditional winemaking method in the Qvevri. In the winery, Baia focuses on typical Imerietian wines from varieties such as Tsitska, Tsolikauri and Krakhuna, while Gvantsa makes red Georgian wines Otskhanuri Sapere, Aladasturi and Ojaleshi.

A testament to her achievement, Baia was recognized in the Forbes’ 30 Under 30 for her work in the vineyards. Today, seven acres of vines filled with indigenous grapes grow without pesticides or fertilizers, tended to with the biodynamic principles, with the most minimal of intervention as the grapes transform into wine.

The Beauty of Baia’s Vineyard

Vineyards on the five-acre family farm are a tangle of weeds, wildflowers, and unfurling vines—a far cry from the usual plucked-and-pruned slopes blanketing much of Europe. Bees buzz and ants skitter between clusters of indigenous grapes destined for Qvevri, where they’ll ferment for a few months with minimal intervention before bottling.

The Village of Obcha in Western Georgia boasts a unique micro-climate, located east of the Sairme Mountains, which receives a slightly higher angle of the sun’s rays with greater solar intensity. At 324 meters above sea level, their land offers an ideal location for growing premium wine grapes. The perfect balance of geography, micro-climate and well-drained soil come together to create the perfect environment for Baias’ exquisitely handcrafted wines. The heavy cold air that collects between the high peaks during the night drains off the heights, much like water, joining cold moist air, creating a double cooling effect. The cool nighttime temperatures are critical in developing high-quality grapes.

Their alluvial soil, with clay, gravel, sand and limestone play a significant role in wine quality, offering good drainage in the wet years while retaining much-needed moisture in the dry vintages.

Biodynamics and Minimal Intervention

“I follow the old traditional methods and rules. They knew what to do and how important the land is,” says Baia, whose grandfather taught her to prune vines and pick grapes according to the moon cycle, a practice common among biodynamic winemakers today. “It’s really powerful to follow the moon. We do not have special equipment and other processes like stabilization by adding chemicals to fall back on.”

Much of Baia’s knowledge comes from their parents, who learnt from their parents. It’s all about family traditions and passing on know-hows from generations to generations. Baia fervently believes in letting nature do most of the work—and working with nature, not against it, which has since become her pillar of success. What started out as a hobby had turned into a huge success, placing Georgia back on the world wine map!